Increasing numbers of jurisdictions are adopting the PSA, due to their belief that it is efficient, cost-effective, and race-neutral. But is it?

By Sarika Ram

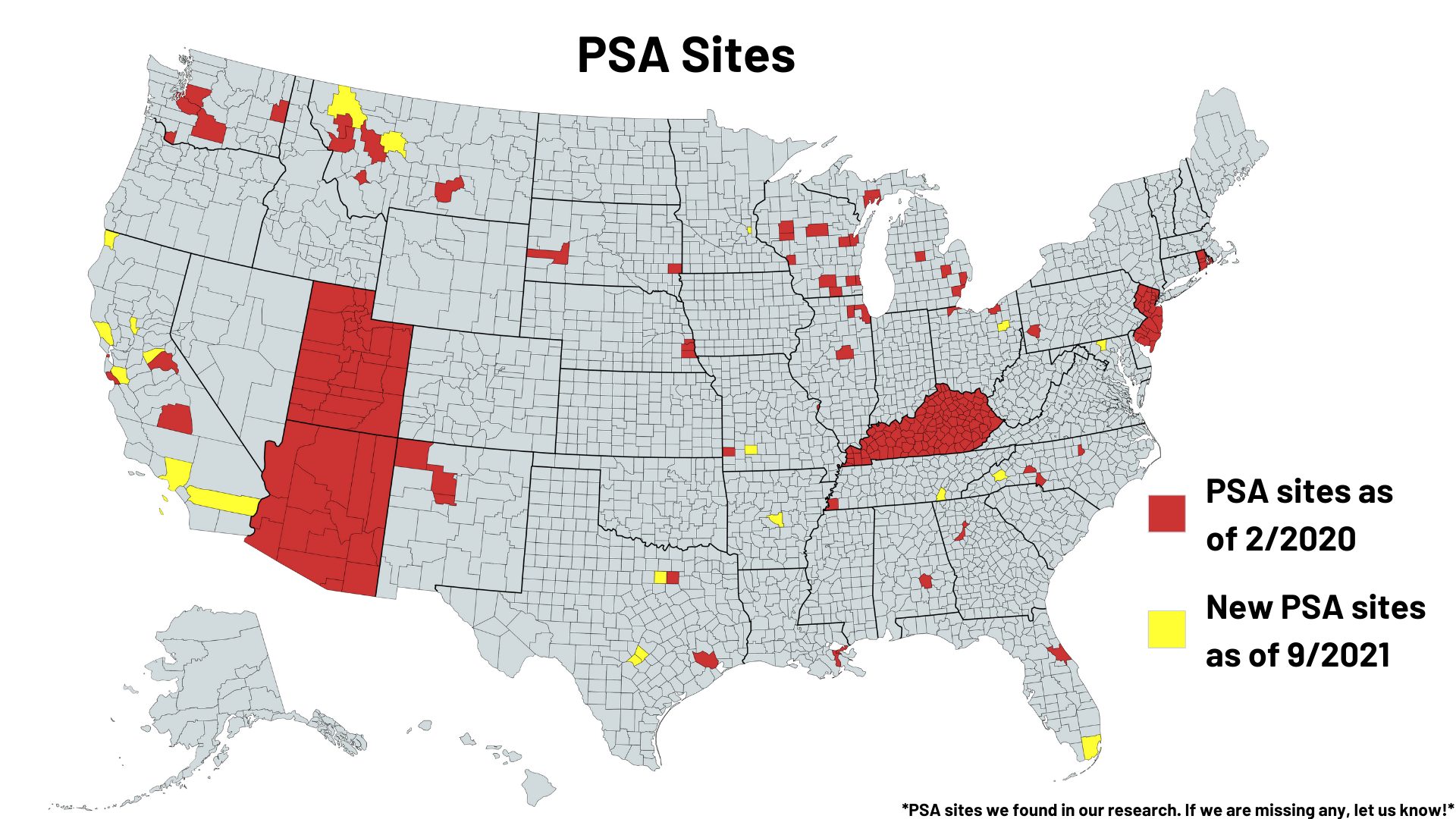

Over the past year, Movement Alliance Project researchers have been updating Mapping Pretrial Injustice, our website that documents where, why, and how pretrial risk assessments are being used across the United States. In our research, we have documented the growing presence of Arnold Ventures’ pretrial risk assessment tool, the Public Safety Assessment, often referred to as the PSA. Since we published our site in February 2020, at least 10 jurisdictions have switched from using either locally-specific homegrown tools, such as the Santa Clara Risk Assessment Tool, or other nationally-developed and widespread tools, such as the ORAS-PAT and VPRAI, to using the PSA. In addition, we found 5 jurisdictions choosing to adopt the PSA for their initial foray into pretrial risk assessment algorithms and 3 jurisdictions newly piloting the PSA as part of a research process.

System stakeholders cite Arnold Ventures’ free technical support, the tool’s relatively low demand on institutional resources, and the algorithm’s exclusion of certain race-correlated variables as justification for switching to the PSA.1Movement Alliance Project Email Communication with Sacramento County Probation Department, August 26, 2021; Sutter County Probation Department, August 19, 2021; Greene County Courthouse, September 2, 2021. Movement Alliance Project Interview with Santa Clara County, September 1, 2021 and Harris County Pretrial Services, 2017.This post explores some of the reasons why so many jurisdictions are turning to the PSA and explains why the PSA doesn’t actually help jurisdictions reach their cost-cutting and racial bias reducing goals, while also regrounding us on why risk assessments are not necessary to release the vast majority of people pretrial.

The PSA is free and includes technical support

Arnold Ventures claims to minimize barriers to implementing a pretrial risk assessment tool by providing complimentary access to both its tool and technical support and resources2Advancing Pretrial Policy and Research: Advancing Pretrial Justice to help localities integrate the PSA into their pretrial decision-making processes. Some jurisdictions said that Arnold Ventures’ rigorous technical assistance informed their decision to switch to the PSA. For example, Harris County adopted the PSA because Arnold Ventures “pays for training and support,” such as review of the jurisdiction’s data.3 Movement Alliance Project Interview with Harris County Pretrial Services, 2017 In a 2017 interview with MAP, one Harris County official said that outside of additional staff planning meetings, they chose the PSA because implementing it required no direct, out-of-pocket costs.4 Movement Alliance Project Interview with Harris County Pretrial Services, 2017

The PSA removes human engagement from the process, saving jurisdictions money

The PSA’s appeal to jurisdictions’ cost-saving interests extends to the design of the tool, which does not require interviews with people awaiting trial. Many pretrial risk assessment tools, such as the ORAS-PAT and VPRAI, require administrators to interview people awaiting trial about their employment status, housing stability, and substance use history, among other factors deemed necessary to evaluating one’s so-called “risk to public safety.” Unlike these tools, the PSA relies exclusively on an automated review of criminal record information, which eliminates the need for staff dedicated to interviewing people awaiting trial. This can be very appealing for jurisdictions trying to cut costs, regardless of its impact on fairness and individualized treatment for people accused of a crime.

Some jurisdictions, including Harris, Sacramento, and Sutter counties, switched to the PSA in an attempt to streamline their pretrial decision-making processes and reduce the significant financial burden associated with administering an interview-based pretrial risk assessment. For example, the Sacramento Probation Department determined that the PSA was the most efficient assessment tool because it does not require interviews, which was important to the Department “given the volume and automation of eligible daily cases requiring pretrial release assessments…”5 Movement Alliance Project Email Communication with Sacramento County Probation Department, August 26, 2021

System actors argued that implementing the PSA not only allowed jurisdictions to process pretrial cases at a faster rate, but that it also allowed counties to process a greater number of cases. For example, prior to implementing the PSA, Harris County’s Pretrial Services Department was only able to assess 80 percent of pretrial cases because the tool in use at the time required an interview.6 Movement Alliance Project Interview with Harris County Pretrial Services, 2017 Switching to the PSA allowed Harris County to evaluate all people awaiting trial with a risk assessment.7 Movement Alliance Project Interview with Harris County Pretrial Services, 2017 In addition to expediting the time it takes to prepare a pretrial report, a representative of the Sutter County Probation Department claimed that the absence of an interview requirement allowed the Department to “mitigat[e] unconscious biases…and eliminat[e] the need for a probation officer to enter the jail during the Covid-19 pandemic.”8 Movement Alliance Project Email Communication with Sutter County Probation Department, August 19, 2021 However, as demonstrated below, there is no evidence that risk assessments in general or the PSA in particular actually do mitigate bias in the pretrial decision making process.

Due to these financial considerations, in some states and counties, officials have argued that localities should switch to the PSA to cut costs. For example, the 2018 Cuyahoga County Bail Task Force recommended that the Cuyahoga Court of Common Pleas switch from the ORAS-PAT to the PSA because “the Arnold Foundation risk assessment tool is simpler (requires less information) than some other risk assessment tools, and Arnold Foundation research indicates it is still as effective in assessing risk. The tool thus does not demand as large of an investment in pretrial services resources as some other tools.”9Jonathan Witmer-Rich, et al.: Cuyahoga County Bail Task Force Report and Recommendations (March 16, 2018) According to a recent MAP communication, the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas still uses the ORAS-PAT and has no plans to switch to the PSA,10 Movement Alliance Project Email Communication with Cuyahoga Court of Common Pleas, July 8, 2021 but this recommendation illustrates how state actors’ pressure to save time and money shape jurisdictions’ decisions about which pretrial risk assessment to use. A 2017 study reviewing Travis County’s implementation of the ORAS-PAT resulted in a similar conclusion. Researchers at the Texas A&M Public Policy Institute argued that while the ORAS-PAT was an “effective decision tool,” counties would be wise to use an automated tool like the PSA because it yields similar results, but without the additional staffing investment.11Dottie Carmichael, et al.: Liberty and Justice: Pretrial Practices in Texas, Liberal Arts Texas A&M University Public Policy Research Institute and Texas Indigent Defense Commission (March 2017)

Cost-saving arguments are wrong – jurisdictions net-widen when implementing a RAT

These arguments touting the PSA for its resource-saving merits—both in terms of the technical assistance that Arnold Ventures offers and the absence of an interview requirement—fail to reckon with the ways in which the tool perpetuates what scholars term “net widening,” which refers to the “process of administrative or practical changes that result in a greater number of individuals being controlled by the criminal justice system.”12David Levinson: “Net Widening“, SAGE Reference MAP’s research shows that jurisdictions that adopt pretrial risk assessment tools often institutionalize mandated face-to-face meetings, electronic monitoring, drug testing, and other forms of correctional control for people who may have otherwise been released on bail or personal recognizance. Several counties in MAP’s research utilize risk evaluations from the PSA to institutionalize a decision-making framework that recommends certain levels of supervision—pretrial release, electronic monitoring, drug testing, or incarceration—for certain risk levels.13Davis County: Pretrial Release Conditions Matrix14New Jersey Courts: Pretrial Release Recommendation Decision Making Framework (March 2018)15Cook County, IL: Public Safety Assessment Decision Making Framework (March 2016)16Denver and Weld County Pretrial Services Programs: Presentation to the Bail Blue Ribbon Commission (August 16, 2018)17Pretrial Justice Institute: The Case Against Pretrial Risk Assessment Instruments (November 2020) Net widening is a harmful phenomenon that entraps a greater number of people, particularly Black and brown, low-income, and LGBTQ+ folks, in the net of the criminal legal system and is a frequent outcome of reformist reforms, such as pretrial risk assessment tools, that fail to even meet state actors’ goals to cut spending.

Consider the example of Cook County and its implementation of the PSA, which increased pretrial electronic monitoring to one of the highest levels in the nation.18Coalition to End Money Bond: Chicago Tribune Editorial Board’s Fearmongering about Electronic Monitoring Threatens Community Safety (May 2021) Cook County, which includes the City of Chicago, developed a decision-making framework that recommends a significant portion of people deemed “high risk” be placed under electronic surveillance.19Cook County, IL: Public Safety Assessment Decision Making Framework (March 2016) The institutionalization of pretrial electronic monitoring requirements has led to a significant increase in the number of Cook County residents who are required to wear a GPS ankle monitor.20Ethan Corey: How a Tool to Help Judges May Be Leading Them Astray, The Appeal (2019) In 2020, there was an average of 3,200 people under electronic monitoring per day in the County, and by 2021, that figure increased by approximately 15 percent to 3,669 people.21MediaJustice: Electronic Monitoring Hotspot Map: Illinois In response to the dramatic increase in electronic monitoring numbers, the Cook County Board approved a $13 million increase to a private GPS electronic monitoring contract in December 2020.22MediaJustice: Electronic Monitoring Hotspot Map: Illinois Though most states and localities require people awaiting trial to pay for their electronic monitors (a harmful practice that deepens the criminalization of poverty), jurisdictions still incur significant equipment, staffing, and infrastructure costs for operating electronic monitoring programs and penalizing people who make technical violations.23Electronic Frontier Foundation: Street-Level Surveillance: Electronic Monitoring States and municipalities also often require that people who violate the terms of electronic monitoring-based release be incarcerated, which undermines efforts to reduce jail overcrowding.24Ava Kofman: Digital Jail: How Electronic Monitoring Drives Defendants Into Debt, ProPublica (July 3, 2019)

The case study of Cook County illustrates how instituting the PSA can contribute to net widening, which is an expensive statewide endeavor that compromises carceral actors’ goal to cut spending. In fact, the best way to cut government spending on pretrial incarceration and supervision is to eliminate it altogether. Pretrial incarceration and other forms of correctional control criminalize poor people who cannot afford to pay bail; harm Black and brown communities, who are disproportionately targeted by the carceral system; unjustly label people as “deserving” or “undeserving” of pretrial freedom; and expand the use of non-monetary conditions (i.e. face-to-face check-ins, drug tests, electronic monitoring) that undermine people’s ability to provide for themselves and their families.25Law & Political Economy: “Bail Reform” & Carceral Control: A Critique of New York’s New Bail Laws (February 2020)26Critical Resistance and Community Justice Exchange: On the Road to Freedom: An Abolitionist Assessment of Pretrial and Bail Reforms (June 2021) If the American criminal legal system is to live up to its promise that all people are innocent until proven guilty, then there is no place for pretrial correctional control.

The PSA claims to reduce racial bias. It does not.

In addition to citing claims that Arnold Ventures’ tool streamlines pretrial decision-making processes and makes them cost-effective, several jurisdictions are also moving to the PSA because it is supposed to eliminate bias. Arnold Ventures argues that its algorithm is race-neutral because it “does not rely on the factors that many are concerned might be discriminatory, such as ethnic background, income, level of education, employment status, neighborhood, or any demographic or personal information other than age.”27Arnold Ventures: Public Safety Assessment FAQs (“PSA 101”) Using a similar line of reasoning, a representative of the Sutter County Probation Department said that the jurisdiction switched from the VPRAI to the PSA because the Arnold tool did not consider socioeconomic factors, such as employment, substance use, and length of time in a residence, unlike the VPRAI.28 Movement Alliance Project Email Communication with Sutter County Probation Department, August 19, 2021 Over hundred miles south, Santa Clara County is in the process of transitioning from a locally developed tool to the PSA, arguing that Arnold Ventures’ tool is “the most neutral tool of all tools” and is “demographically blind, as far as everything except age.”29 Movement Alliance Project Interview with Santa Clara County, September 1, 2021

Arnold Ventures and institutional actors tout the PSA for excluding race-correlated input variables, like home ownership and employment status. However, the exclusion of these variables does not absolve the PSA of perpetuating racial disproportionality. The tool includes and heavily weighs one’s criminal history, which is shaped by the carceral system’s legacy of systematically targeting communities of color. In “Bias In, Bias Out,” law professor Sandra Mayson argues that the reformist call to eliminate race-correlated variables from pretrial risk assessments fails to reckon with the fundamental nature of prediction. As Mayson writes, “Prediction looks to the past to make guesses about the future. In a racially stratified world, any method of prediction will project the inequalities of the past into the future.”30Sandra G. Mayson: Bias In, Bias Out, Yale Law Journal (2018)

Mayson’s argument is borne out by early research and data on the Public Safety Assessment. After adopting the PSA statewide in 2017, New Jersey saw overall decreases in its state jail population, but the “racial and ethnic makeup within New Jersey’s jail population has remained largely the same,”31Glenn A. Grant: Jan 1-Dec 31 2018 Report to the Governor and the Legislature, New Jersey Courts, Criminal Justice Reform (2018) calling into question the claim that the PSA is race-neutral and a “solution” to racial disparities in incarceration.” Researchers examining the implementation of the PSA in Mecklenburg, North Carolina found that the tool had no clear impact on racial disparities in their jails, and Black people awaiting trial were more likely to be deemed high risk relative to their non-Black counterparts.32Cindy Redcross, Brit Henderson, Luke Miratrix, and Erin Valentine: Evaluation of Pretrial Justice System Reforms that use the Public Safety Assessment: Effects in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, MDRC Center for Criminal Justice Research (2019) In Kentucky, the statewide adoption of the PSA exacerbated racial disparities in non-financial pretrial release. Before the implementation of the Arnold Ventures’ tool, the gap between White and Black people released on personal recognizance was 2 percentage points. After the implementation of the PSA, this gap increased to 10 percentage points.33Megan Stevenson: Assessing Risk Assessment in Action, George Mason University (2017)

Despite how jurisdictions moving to the PSA claim the tool will make their systems more efficient, cost-effective, and unbiased, the data has not borne that out. The Public Safety Assesment’s dominance also illustrates the insidious ways in which private corporations—namely Arnold Ventures—co-opt the language of racial equity and justice, evidence-based science, and decarceration to legitimize and expand the role of the carceral system. The solution for pretrial systems to be more efficient, cost-effective, and unbiased is to make pretrial incarceration extremely rare, not automate the decision making around it.